You don’t need a degree to contribute to cutting edge scientific research on proteins. As it turns out, all you need is your ability to solve puzzles more intuitively than a computer can. Despite recent media fuss over supercomputers like Watson, which have the ability to answer complex questions, the human mind still has an edge when it comes to efficiently recognizing and sorting out visual problems.

Sorry, Watson. Can we still be friends?

This emergence of using human minds to assist computers, almost counterintuitive in a culture of Google and smartphones, owes itself to a technique known as “crowd-sourcing.” Essentially, crowd-sourcing is an open request to the public for assistance on enormous tasks.

Scientific researchers have been tapping into crowd-sourcing technology for years now. But they’ve tweaked it to suit their field, creating a phenomenon called “citizen science”. Involvement typically requires no special scientific knowledge, and researchers design tasks with the assumption that average people will help complete them.

A few years ago, a project called Foldit invited the public to help tackle the mysteries of protein structure with an online puzzle game. A single machine sat at work on the problem at first, flashing its progress across a screen in the scientists’ lab. Foldit capitalizes on a moment when the lab's visitors began suggesting obvious ways to fold proteins, even as the software struggled.

I logged into the Foldit interface and after a few minutes of training, I was eagerly untwisting side-chains, forming hydrogen bonds, and wiggling the protein’s backbone until it was stable. It felt more like a game of Tetris than a lesson in molecular structure, and each completed protein ushered me into a new level with extra points for my best fold designs. Despite my enthusiasm, I was turning out some pretty unimpressive totals. But the game’s creators hope that top-scoring players might be able to take a virtual copy of a virus, like HIV, and form a deactivating protein around it. Researchers can then synthesize the best user-created

designs and test them for real in a lab. Players, of course, will be credited.

Foldit screenshot.

Or maybe proteins aren’t really your style. You could align colorful sequences of DNA (all of which are segments that have been linked to a genetic disorder) with Phylo, a game similar to Foldit. If you’d really like to sit back and relax, just contact the Cloned Plants Project to plant a lilac and agree to observe its characteristics over time. Scientists will use the data you collect to monitor the plant’s response to climactic change on a worldwide scale. For the festive ornithologists out there, you could participate in the Audubon’s society’s annual Christmas Bird Count. You’ll join over ten thousand volunteers in recording bird populations, and your numbers will fuel conservation research.

Users solving multiple sequence alignment problems with Phylo.

By now I'm sure you’re thinking, “Play games for science! That’s great!”

But how much is it really helping? There’s still a bit of work to be done before we'll discover how much people can realistically aid in something as complicated as protein synthesis. Yet, the success of other ventures suggests that we have something to be optimistic about. A project called Galaxy Zoo, which in 2007 asked its participants to identify millions of galaxies in telescope images, found that classifications provided by user data were just as accurate as those given by professional astronomers. Last month, a group of scientists facing a tight deadline and inadequate resources turned to their Facebook friends for help identifying over 5,000 fish specimens. Most of the work was finished within a day.

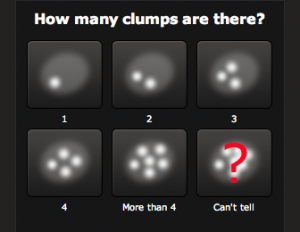

A screenshot of Galaxy Zoo question to users, who

assist in classifying galaxies.

Science from your iPhone.

Simply put, citizen science gets things done- and quickly. More importantly, though, most projects aim partly to connect with their participants in a meaningful way. Foldit brings ordinary people closer to the advancements that they demand from the sidelines, like cures for diseases. It seizes the surprisingly underrated strength of personal experience as a tool for collaborative education. After all, what better way is there to make a person care about a topic than to involve him in it directly? And it reminds us of the value of the human mind, even as we move to expand beyond it with amazing feats of technology.

Besides all that, it’s fun. Everyone wins, except maybe the midterm paper you’ve abandoned in your obsessive quest to rack up the protein-folding points. It’s okay. There will be plenty of papers to write after you fold, match, and twist your way to a cure.

Song of the Day.

Codex- Radiohead

Oblivious person that I occasionally am, I missed the recent release of this (much sleeker) sister-project of Foldit, EteRNA.

ReplyDelete