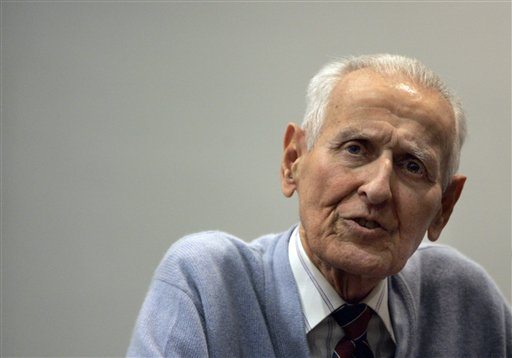

Dr. Jack Kevorkian passed away today, but his ideas have done more for bringing the topic of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide to the forefront of modern bioethics than any other's.

I wrote a final paper about euthanasia not long ago, and I think it would be fitting to post it now. It's an issue I've found to be quite impassioning, which is also why it deserves a more prominent place in contemporary debate.

Jack Kevorkian, 1928-2011

Moral Permissibility of Active Euthanasia

Dr. Kevorkian, Terri Schiavo, and Karen Quinlan are three of the most controversial names in modern bioethics because of the roles they played in landmark euthanasia cases. Their presence in our society is part of a greater reflection on whether euthanasia’s etymological meaning of, “good death” is befitting of the process it represents. Some wrestle with the idea that euthanasia really spans two morally distinct categories- active, in which lethal treatment is administered, and passive, where life-sustaining treatment is simply stopped. Often, active euthanasia is viewed as, “killing”, and passive as, “letting die.” From this point, ethicists debate if one type of euthanasia should be preferred over another or if one should be disallowed altogether. I argue here that there is no useful distinction between “killing” and “letting die”, and that active euthanasia is morally preferable to passive.

Much has been made of whether a moral difference between active and passive euthanasia exists. Right from the start, some question whether the passive form deserves the title of euthanasia at all. J. Gay-Williams argues that withholding treatment from a terminally ill patient constitutes an unintended death rather than an act of killing (Munson 704). Euthanasia, then, refers exclusively to the active form that Gay-Williams condemns. He provides an example of the lack of intention that he believes defines passive euthanasia, saying, “When I buy a pencil it is so I can use it to write, not to contribute to an increase in the gross national product. This may be the unintended consequence of my action, but it is not the aim of my action … I intend his death no more than I intend to reduce the GNP by not using medical supplies,” (Munson 704). If the patient’s death is not the aim of Gay-William’s actions, what would he say is? The main consequence of halting treatment in a dying patient is the immediate and absolute decline of the person’s health. This outcome is certain, and the consequence of the action is so intuitively close to the action itself that it does not compare to the abstract, highly removed economic repercussions of buying a pencil. His logic wrongly neglects the moral heart of the situation. Yes, the doctor aims simply to shut off the machine. Likewise, his only intent following that is to do nothing. It is true that none of his actions taken singly cause the patient’s death. It is inappropriate, however, to isolate an action when it is known to be part of a complex system. Context is crucial; doing nothing after eating dinner is incredibly different from doing nothing after dismantling someone’s life-saving treatment. It doesn’t make sense in this situation to claim that I don’t also aim to enact the best interests of the patient in allowing his life to end.

Gay-Williams has little basis for his argument because the outcome of any form of euthanasia could be reasonably expected. Suppose that I have a finch in a cage. If I leave the door of the cage open, I could say that I only intend to open the door. But when the bird escapes and I find it flying around the room, it would be bizarre to feel great surprise. Now suppose that this bird is also my neighbor’s beloved pet. Would she be any less reasonable in blaming me if I insisted that I only meant to open the door? I didn’t physically create the movement in the bird’s wings that allowed it to fly away, but it doesn’t bear much relevance to this situation because I still helped the bird escape.

Daniel Callahan proposes another set of arguments, only slightly different from Gay-Williams’. He writes that, “it confuses reality and moral judgment to see an omitted action as having the same causal status as one that directly kills” (Munson 708). With this, Callahan introduces the idea of another distinction –causality versus culpability. Causality relates to, “direct physical causes of death,” whereas culpability refers to, “our attribution of moral responsibility to human actions” (708). Yet like Gay-Williams, Callahan overlooks an important point. Culpability is the practical deciding factor here, where causality exists as more of an abstract consideration. There is no moral difference between active and passive euthanasia because the culpability is constant in both situations; that is, the doctor is not morally to blame for the unfortunate death of his patient in either type of euthanasia. Again, this lies in the inevitability of the patient’s death in the face of the doctor’s choice of action. When I accept my implicit culpability in the outcome of my patient, causality is only one of many factors taken into consideration. Assigning equal weight to causality and culpability is like placing the first draft of a paper on equal footing with its final, edited form; you wouldn’t judge the incomplete draft because it lacks the rest of the necessary components that eventually comprise the end product. Similarly, you need to combine causality with other situation-specific elements to determine culpability, which is what ultimately matters. In James Rachel’s terms, “the bare difference between killing and letting die does not, in itself, make a moral difference… If [the doctor’s] decision was wrong –if, for example, the patient’s illness was in fact curable –the decision would be equally regrettable no matter which method was used to carry it out” (Munson 727). So, while Callahan is perhaps correct to argue that there are definitional, causal differences separating active and passive euthanasia, he is wrong to imply that they are relevant ones.

Part of the logic in denying a significant moral difference between methods of euthanasia involves demonstrating that the active variety is just as right as the passive, assuming that you permit at least the passive form. We may recall that those who draw a distinction sense a factor of “killing” in active euthanasia and reject it. Sometimes, however, “killing” is justified; in this case, it may even be preferable. First, we must consider whether there is something inherently wrong in causing death if we are not culpable for it. Rachels remarks that, “The reason why it is considered bad to be the cause of someone’s death is that death is regarded as a great evil –and so it is” (Munson 728). It seems that the only thing we recognize (and Rachels notes it) is that death is so tragic and final that to press our faces to its window and peer inside is to admit guilt by association, because we should have looked away. Our uneasiness with death causes hesitation, and Grant Gillett explains the intangible “pause” that doctors often feel in these cases. He uses the “pause” to defend their unwillingness to administer lethal treatment (Gillett 61). Howard Brody denies his point, saying, “the fact of ‘the pause’ simply means that morally sensitive agents are dealing with difficult problems, and that cannot be used by itself as an argument for one side or the other of the argument”(Brody 46). Doyal, too, acknowledges that there is something flawed with focusing on the aspect of death before that of its potential moral good –“ if death is in the best interest of some patients –if the withdrawal of life sustaining treatment can be said to be of benefit in this case –then death constitutes a moral good for these patients. And if this is so, why is it wrong to intend to bring about this moral good?” (Doyal 1079). Even if something within us takes initial pause at the idea (Gillett’s “pause”), there is nothing real to prevent us from actively causing death if it enacts a moral good that would have otherwise enacted itself.

Why do we not allow this moral good to enact itself? That is, if we are justified in interfering, should we do so? Suppose that two friends, Tom and James, enter as a team into a wilderness survival exercise. The rules of the excursion state that no modern tools, like lighters, may be used. Sometime during the day, Tom and James mistakenly lose their group and find themselves actually stranded in the wild. Tom has a lighter in his pocket, though he had never planned to use it in the exercise. They need to build a fire, and James suggests using the lighter. Tom disagrees, saying that the rules would prohibit it. So, the men struggle for days to light a fire from scratch. They finally manage to get a flame going, but in the time it has taken them to do so they have endured hypothermia, a lack of cooked food, and all the suffering that those things entail. James should be quite upset with Tom, because he caused them both needless suffering. If Tom knows that, either way, a fire would be the expected and intended outcome of their efforts, he is wrong to allow the option that increases suffering. He is especially wrong to follow the activity’s rules when they do not really apply to a universal condition. Tom and James can certainly prepare for the worst, but they would be absurd to prefer it if other options exist. Similarly, it would seem curious for a doctor who aims to accelerate the death of his patient to dilute his efforts by waiting for a natural death to occur after taking the first steps in allowing it. Passive euthanasia, according to Rachels, “endorses the option that leads to more suffering rather than less, and is contrary to the humanitarian impulse that prompts the decision not to prolong his life in the first place” (Munson 726). It is incorrect to remove ourselves so far from this humanitarian impulse in favor of philosophical abstraction, for excellent philosophy remains objective while also being practical.

Consider a moment in Voltaire’s Candide when, after approaching a town that has just been destroyed by an earthquake, the philosopher Pangloss analyzes the situation instead of attempting to deliver any meaningful help (Voltaire 18). His delay is inappropriate to the circumstances. Pangloss isn’t at fault for the current condition of those struggling beneath the rubble, but he does deny them the sense of urgency that they deserve. He now perpetuates suffering needlessly, like a doctor who refuses to act immediately in bringing about the desired end of a terminally ill patient’s life. I don’t mean to belittle the incredibly difficult situation the doctors must face with a comparison to Voltaire’s satirical character, but it must be clear that there can be no benefit to the additional suffering involved in passive euthanasia. Suffering is not, as Gay-Williams writes, “a natural part of life with values for the individual and for others that we should not overlook” (Munson 706). It is a very serious consequence to passive euthanasia that is taken far too lightly.

Passive euthanasia, and the waiting for death that it entails, is unacceptable particularly because if we appeal to our basic human instincts, it is difficult to justify optional suffering. When we place ourselves in the situation of the patient fated to death, we would hope for compassion in the form of death’s swift, painless fulfillment. It is easy to debate from a position of privilege, like Pangloss above the debris. But it is a more humane and, I think, useful position to immerse ourselves, if only for a moment, beneath that debris and absorb the view.

Thus, it becomes increasingly clear through reflection on the matter of euthanasia in practical terms that any difference between active and passive forms that may exist is irrelevant to our moral consideration. Because of its insignificance to the basic morality of euthanasia in general, we can examine the comparable values of the two types without regard to any definitional differences between them. Active euthanasia achieves the same end as passive while favoring a condition of less suffering and should therefore be preferred. Despite this conclusion, active euthanasia still has largely to be accepted, yet alone preferred in contemporary medicine. It is therefore vital that this discussion continues, so that it at least actively challenges what may be a flawed current state of affairs in a life or death issue.

Thus, it becomes increasingly clear through reflection on the matter of euthanasia in practical terms that any difference between active and passive forms that may exist is irrelevant to our moral consideration. Because of its insignificance to the basic morality of euthanasia in general, we can examine the comparable values of the two types without regard to any definitional differences between them. Active euthanasia achieves the same end as passive while favoring a condition of less suffering and should therefore be preferred. Despite this conclusion, active euthanasia still has largely to be accepted, yet alone preferred in contemporary medicine. It is therefore vital that this discussion continues, so that it at least actively challenges what may be a flawed current state of affairs in a life or death issue.

Bibliography

- Brody, Howard. “Correspondence: Euthanasia, Letting Die and The Pause.” Journal of Medical Ethics. 15.1 (1989): 46.

- Doyal, Len and Lesley. “Why Active Euthanasia And Physician Assisted Suicide Should Be Legalised: If Death Is In A Patient's Best Interest Then Death Constitutes A Moral Good.” British Medical Journal. 323.7321 (2001) 1079-1080.

- Gillett, Grant. “Euthanasia, Letting Die and The Pause.” Journal of Medical Ethics. 14.2 (1988): 61-68.

- Munson, Ronald. Intervention and Reflection: Basic Issues in Medical Ethics. 8th ed. Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth, 2008.

- Voltaire. Candide. Fairford: The Echo Library, 2009.

No comments:

Post a Comment